Table of Contents

This guest essay by Daniel Parris was originally published on June 12, 2024 in Stat Significant, a free weekly newsletter featuring data-centric essays about movies, music, and TV that we cannot recommend highly enough. We felt that this would be a good companion to Andy Singer's more sanguine look at the future of content.

Intro: A Finale Capable of Destroying Public Infrastructure

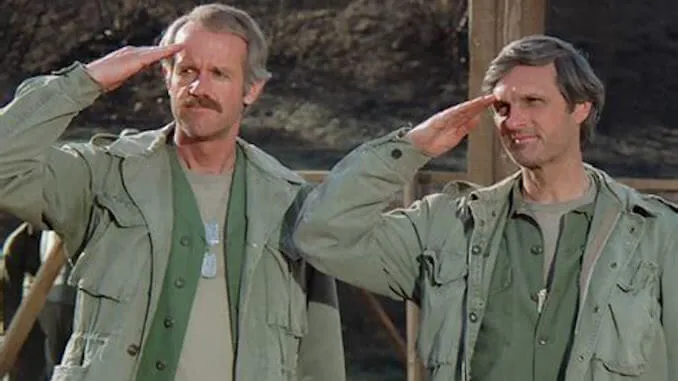

The 1983 series finale of "MAS*H" remains one of the most significant cultural events of the 20th century, only surpassed in reach by Super Bowl broadcasts and the Moon Landing. Anticipation for the series send-off was unprecedented, with CBS charging advertisers a reported $450,000 per 30-second ad slot (equal to $1,416,632 today)—exceeding the ad costs of that year's Super Bowl.

[Image: "M*AS*H" (1972). Credit: CBS]

The finale aired on February 28, 1983, and became the most-watched television episode in US history with an audience of over 121 million. Immediately after the finale's conclusion, New York City experienced a significant drop in water pressure due to a massive, simultaneous flush of toilets across the city. This phenomenon occurred as over one million New Yorkers, who had held off using the bathroom during the broadcast, rushed to the toilet and flushed seconds after the show's conclusion. A city spokesman from the Department of Environmental Protection classified the event as unreproducible: "We don't know of any instantaneous increase in water usage that would match [the 'MAS*H' finale]."

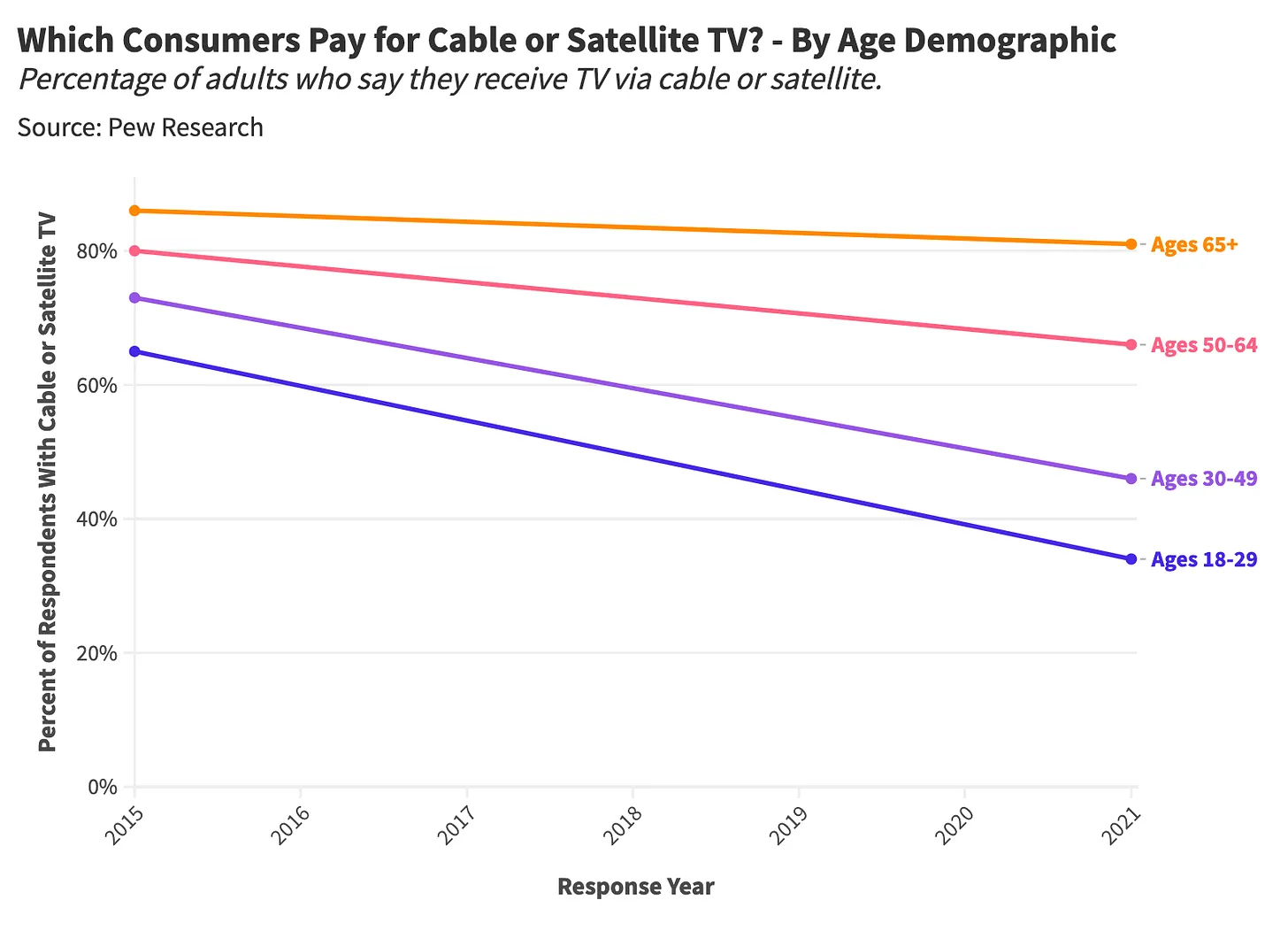

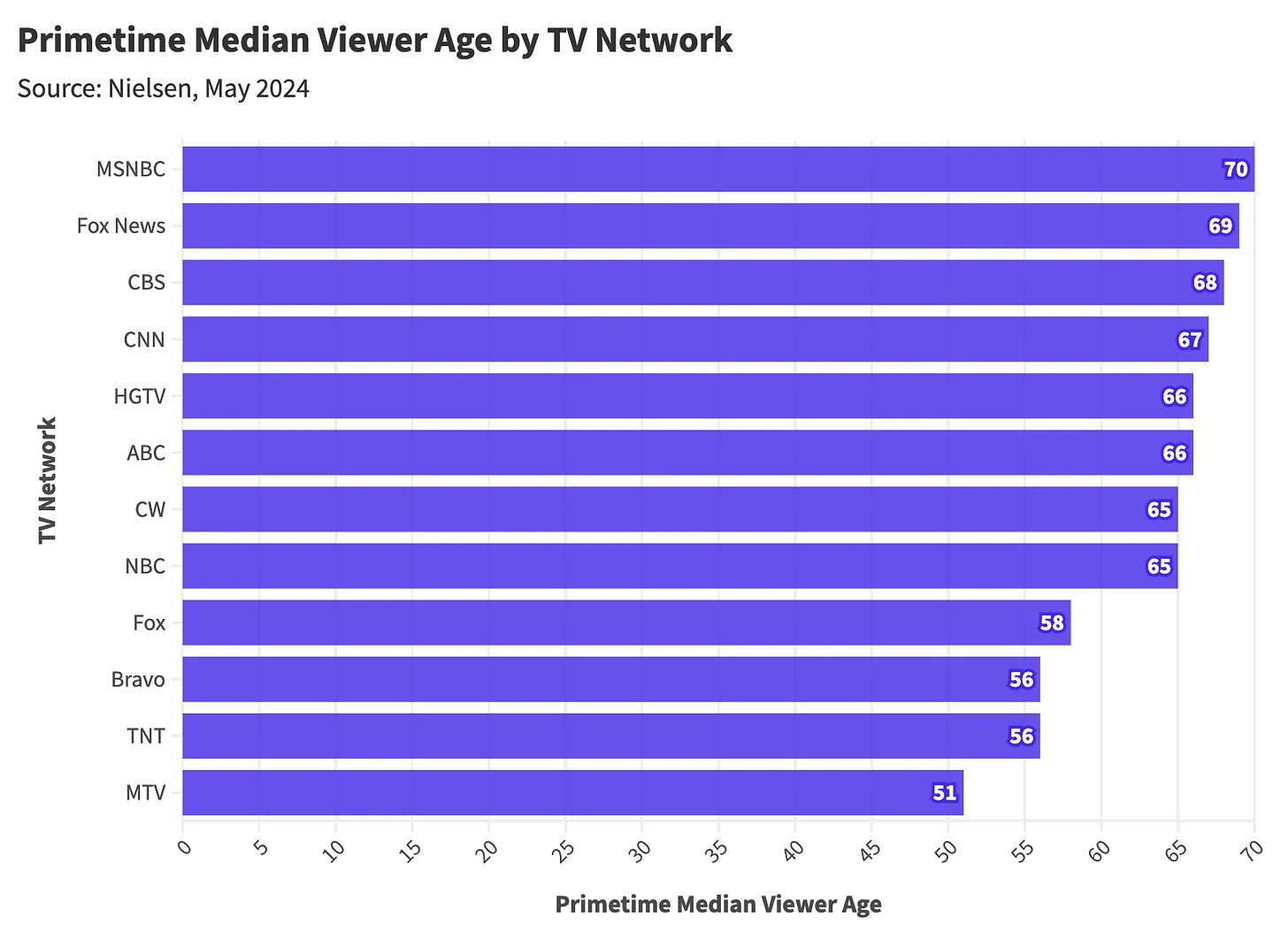

Fast-forward to three weeks ago, when the analytics firm Nielsen released data indicating that the median viewer age for cable and broadcast TV is 64.6. A once-universal medium capable of wrecking New York's public infrastructure could now be considered increasingly niche, its user base skewing older.

Cable's aging audience isn't surprising, as TV watchers have increasingly cut the cord in favor of streaming services like Netflix and Hulu. Most astonishing to pundits was the sheer magnitude of this demographical shift, a testament to ever-accelerating declines in cable subscribership.

As of 2023, a reported more than 50 million households pay for cable, broadcast, or satellite television, which begs a simple question: What are these streaming hold-outs watching, and how has network programming adjusted to its shifting audience?

So today, we'll explore the ongoing collapse of linear television, how pay TV's audience demographics have changed over the past decade, and what we've lost amidst cable's decline.

A Brief History of Linear TV's Rise and Fall

Britain's BBC carried out the first consumer television broadcast on November 2, 1936. The telecast featured a variety show led by singer Adele Dixon and a performance by the BBC television orchestra. The broadcast's audience consisted of early adopters in the London metro area, primarily wealthy individuals.

[Image: The BBC’s first broadcast in 1936. Credit: BBC]

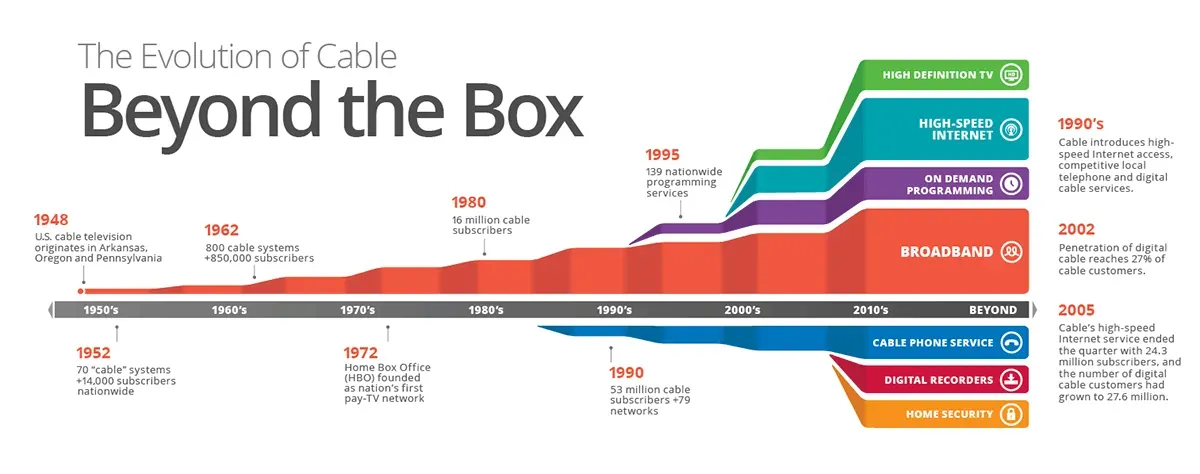

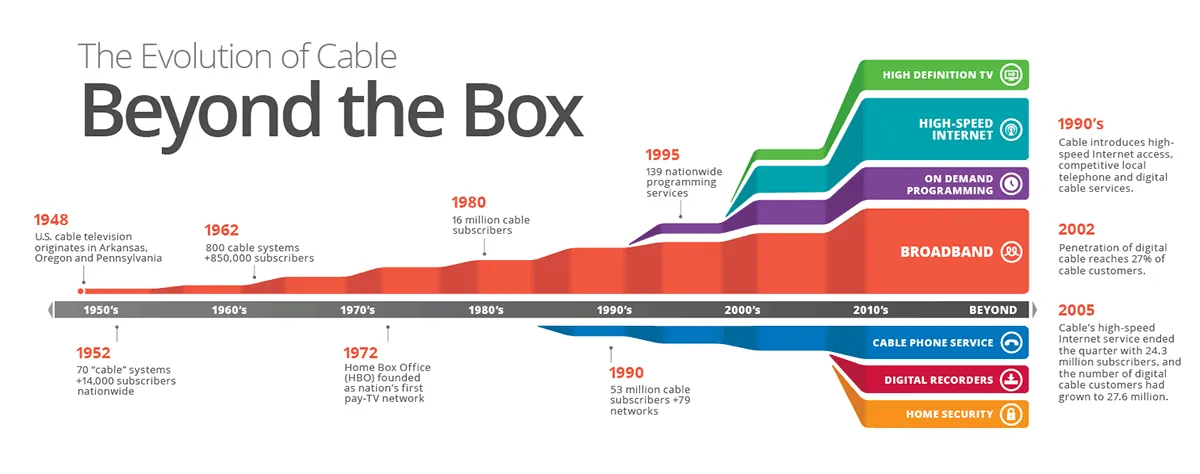

Home entertainment would evolve rapidly over the next ninety years, marked by distinct eras of technological advancement and programming innovation:

- The "Golden Age" of Television (1940s — 1960s): The post-WWII period saw the rise of commercial broadcasting with the introduction of major networks like NBC, CBS, and ABC and an explosion of popular programming genres, including sitcoms, dramas, news, and variety shows.

- Color Television and Programming Expansion (1960s — 1980s): This era saw a transition to color broadcasting in the early 1960s, the advent of satellite TV, which enabled global news networks like CNN, and the growth of a cable TV ecosystem that featured specialized channels like ESPN and HBO.

- Digital and High-Definition Television (1990s — 2000s): In the late 1990s and early 2000s, there was a shift from analog to digital broadcasting, which improved audiovisual quality (high-definition was introduced) and enabled program recording.

- Streaming and On-Demand Services (2010s — Present): The rise of internet streaming services like Netflix and Hulu and their significant investment in original (prestige) content led to "cord-cutting" and the decline of cable, satellite, and telco (these services are often referred to as "pay TV").

These last two periods have proven remarkably transformative, altering home viewership habits (i.e., Netflix and chill, binge-watching, etc.) while also cannibalizing the appeal of moviegoing. A diagram of cable's 80-year evolution by The California Broadband Association shows an acceleration of technological progress starting in the 1990s, marked by a surge in high-end home entertainment products and high-speed data transmission.

[Source: The California Broadband Association]

That said, this chart omits perhaps the most consequential innovation of the last two decades: the introduction of television streaming.

Netflix launched its streaming service in 2007, initiating its transition from a DVD rental business to a digital content platform. The streaming pioneer began producing original content in 2013, debuting splashy shows like David Fincher's "House of Cards" and Jenji Kohan's "Orange Is The New Black," thus setting a new standard for programming quality.

[Image: "Orange Is The New Black" (2013). Credit: Netflix]

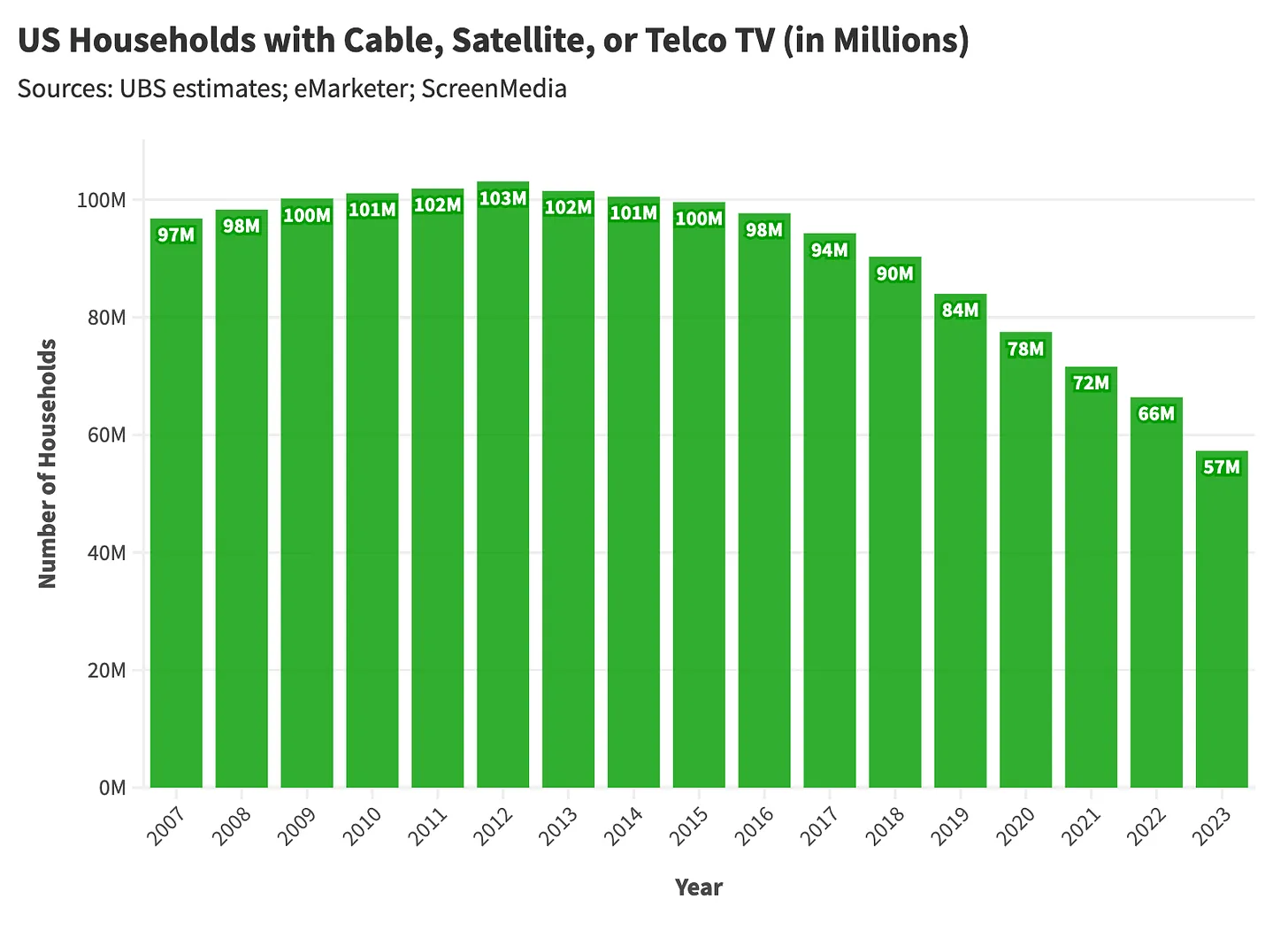

Pay TV adoption peaked in 2012, a year before Netflix's foray into original content, and has since experienced eleven consecutive years of subscriber declines. As of 2023, the number of households with cable, satellite, or telco TV has decreased by 44 percent compared to its 2012 high.

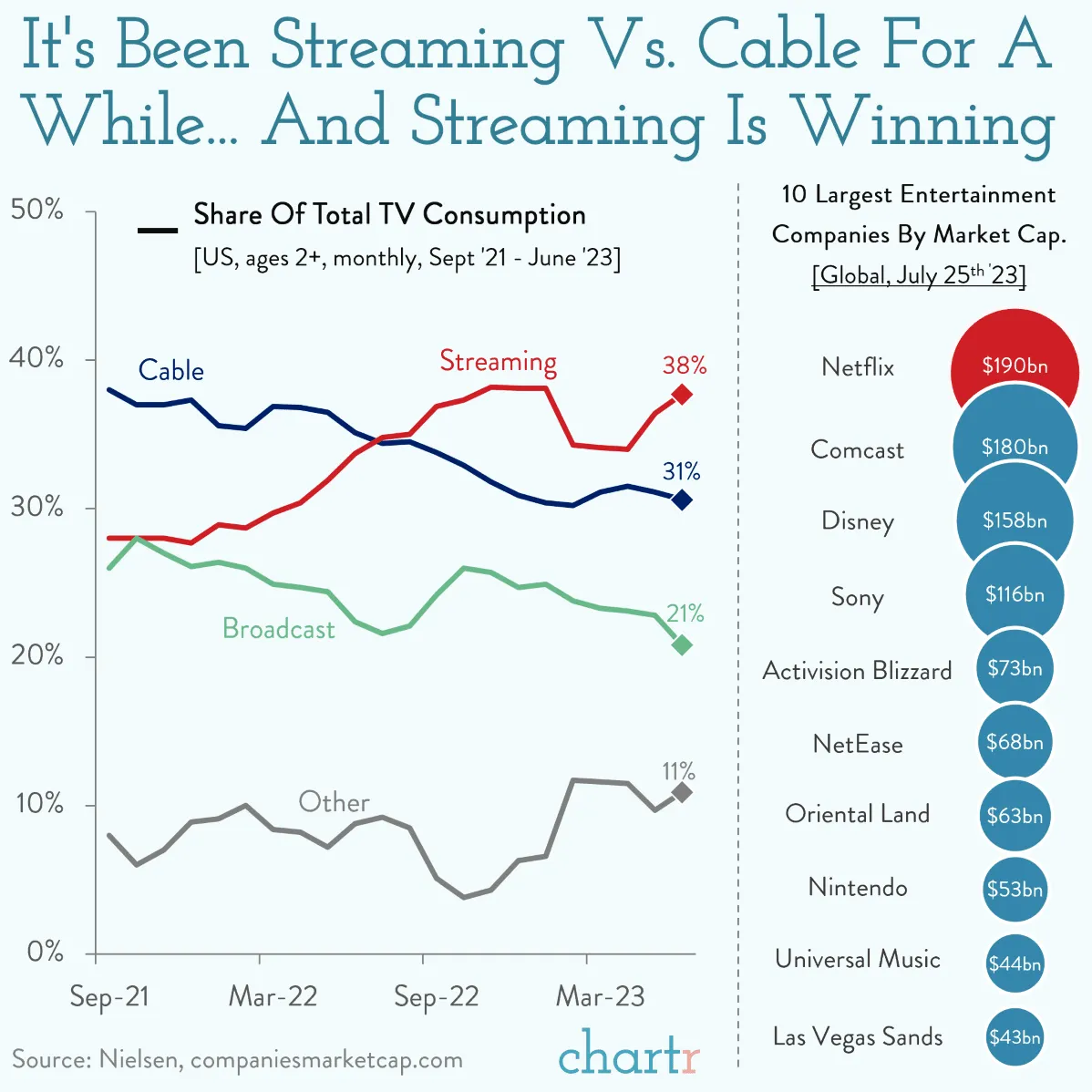

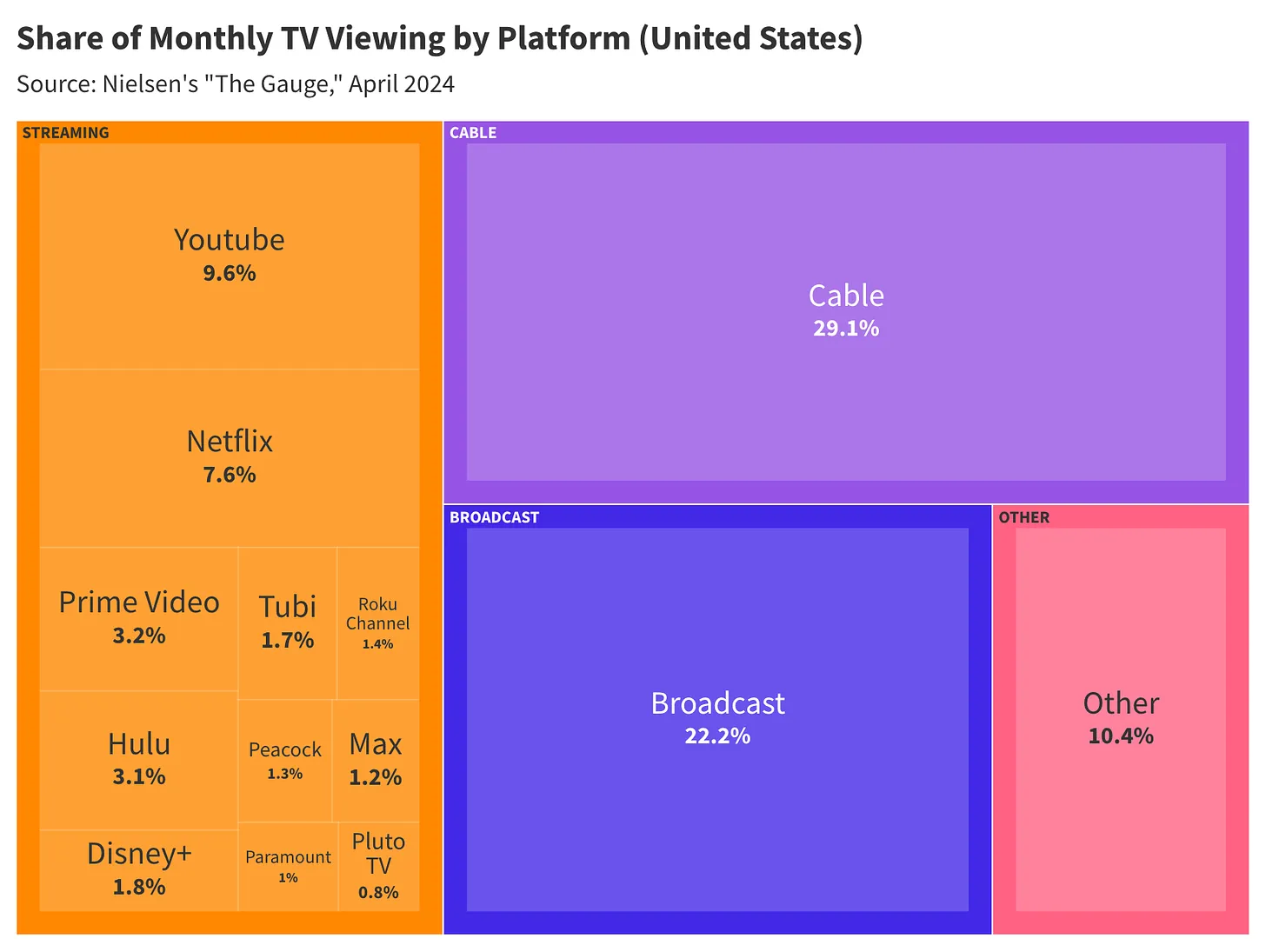

In the summer of 2022, streaming passed cable as the predominant mode of TV consumption in the United States, and Netflix became the most valuable entertainment company (in human history?).

[Source: Chartr]

This data will not be shocking to most—it's no secret that Netflix and streaming have sufficiently swallowed the film and television industries. What's fascinating here is the sheer pace of technological change. Streaming saw accelerated adoption as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, fueled by low subscription prices, an excess of free time (at home), and an ever-proliferating ecosystem of prestige content.

Such rapid progress inevitably produces a cohort of laggards—consumers who resist adoption or simply refuse. Maybe this group finds little appeal in streaming's value proposition, or perhaps they're unfamiliar with the splendor of Netflix's content library (and now they're missing out on shows like "Is it Cake?" and "Too Hot to Handle"). So what do these streaming hold-outs watch? What programming satiates these customers in place of streaming gems like "Deal or No Deal Island" and "Squid Game: The Challenge"?

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content? Subscribe to Stat Significant for free, and receive new data essays every week.

The Remains of Pay TV and The Death of Monoculture

One of the biggest differences between pay TV and streaming is linearity; with cable and broadcast, you must watch or record a program that airs at a set time. In most cases, this temporal constraint is a hindrance, regulating what viewers watch and when—except when it comes to live sports.

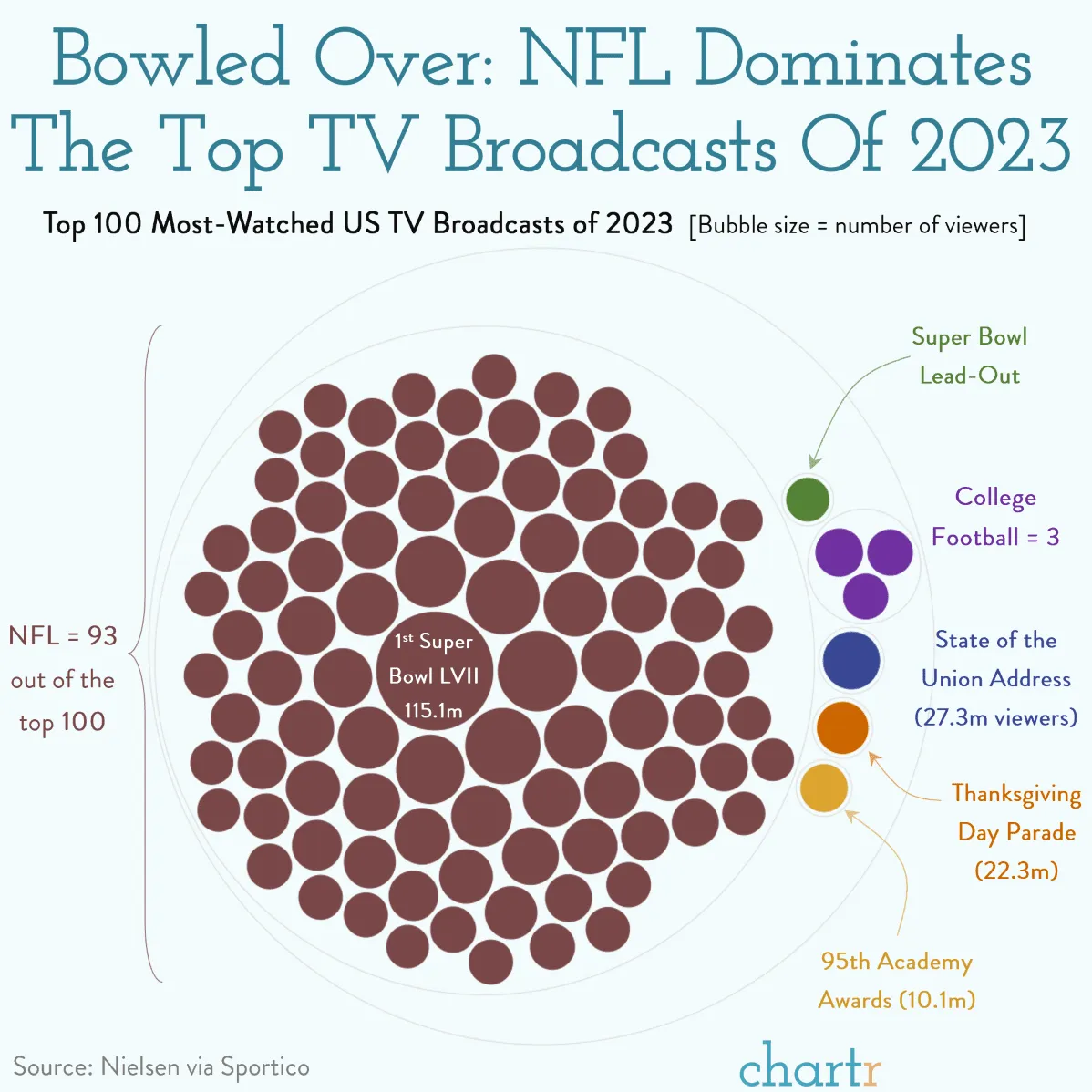

Ninety-three of the top 100 US TV broadcasts of 2023 were NFL football games, and many of these programs were blowouts or contests between terrible teams. Said differently, broadcast television is being propped up by live sports viewership—a distinct use case when linearity makes sense.

[Source: Chartr]

But, alas, these lucrative sporting telecasts are now migrating to streaming.

Next year, NFL streaming rights will be divided across five platforms, with Netflix entering the live sports market to stream a handful of games. When football season starts in September of this year, I will be forced to un-cancel my Peacock subscription and subscribe to ESPN+ — an unfortunate reality I have yet to fully accept. At this point, my football fandom is being taxed by various streaming services, much like buying alcohol or cigarettes. The NFL and NBA's move to streaming nullifies cable's last competitive advantage; for consumers, this means replacing one linear subscription with five streaming services.

As cable's value proposition has diminished, younger viewers have opted out of their contracts, while older consumers have primarily stuck with legacy providers.

This shift leaves linear television with an ever-aging cohort of viewers.

According to Nielsen, news networks like CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC attract viewers who are (on average) in their late 60s. Meanwhile, networks targeting "younger" audiences, like MTV and Bravo, regularly appeal to viewers in their early to mid-50s.

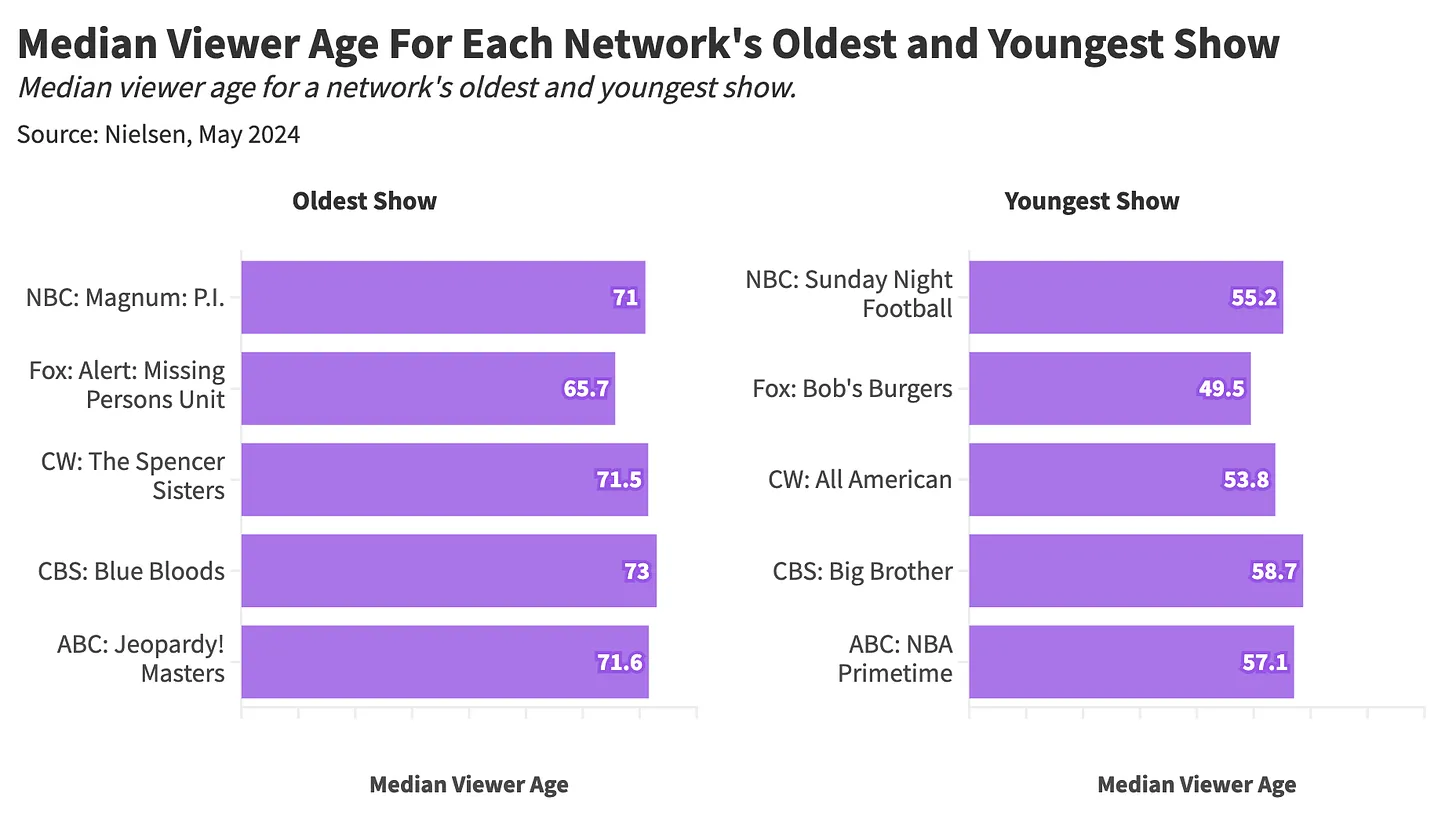

When we look at each network's oldest and youngest show (as a function of median age), we find primetime programs like "Blue Bloods" and "Magnum P.I." typically bring in viewers in their 70s, while "younger" series like "Bob's Burgers" and "Big Brother" attract audiences in their early 50s.

The initial takeaway from this data is pretty straightforward: pay TV viewership is rapidly aging. Each medium is now associated with a distinct demographic: cable skews older, and streaming skews younger. But behind these demographical trends lies an unfortunate truth about the increasing fragmentation of modern media, an entertainment landscape defined by disparate content silos.

Consider Nielsen's monthly gauge of TV consumption by distribution channel, which breaks down viewership across platforms (cable, streaming, etc.) and services (Netflix, Disney+, etc.). Eleven prominent streaming services have emerged over the last ten years, spreading TV consumption across an ever-expanding array of mediums, channels, and streamers.

With the exception of a live football broadcast or Oscar ceremony, few people watch the same thing at the same time. Cable and broadcast television were inconvenient for numerous reasons, but they also fostered a sense of communal viewership.

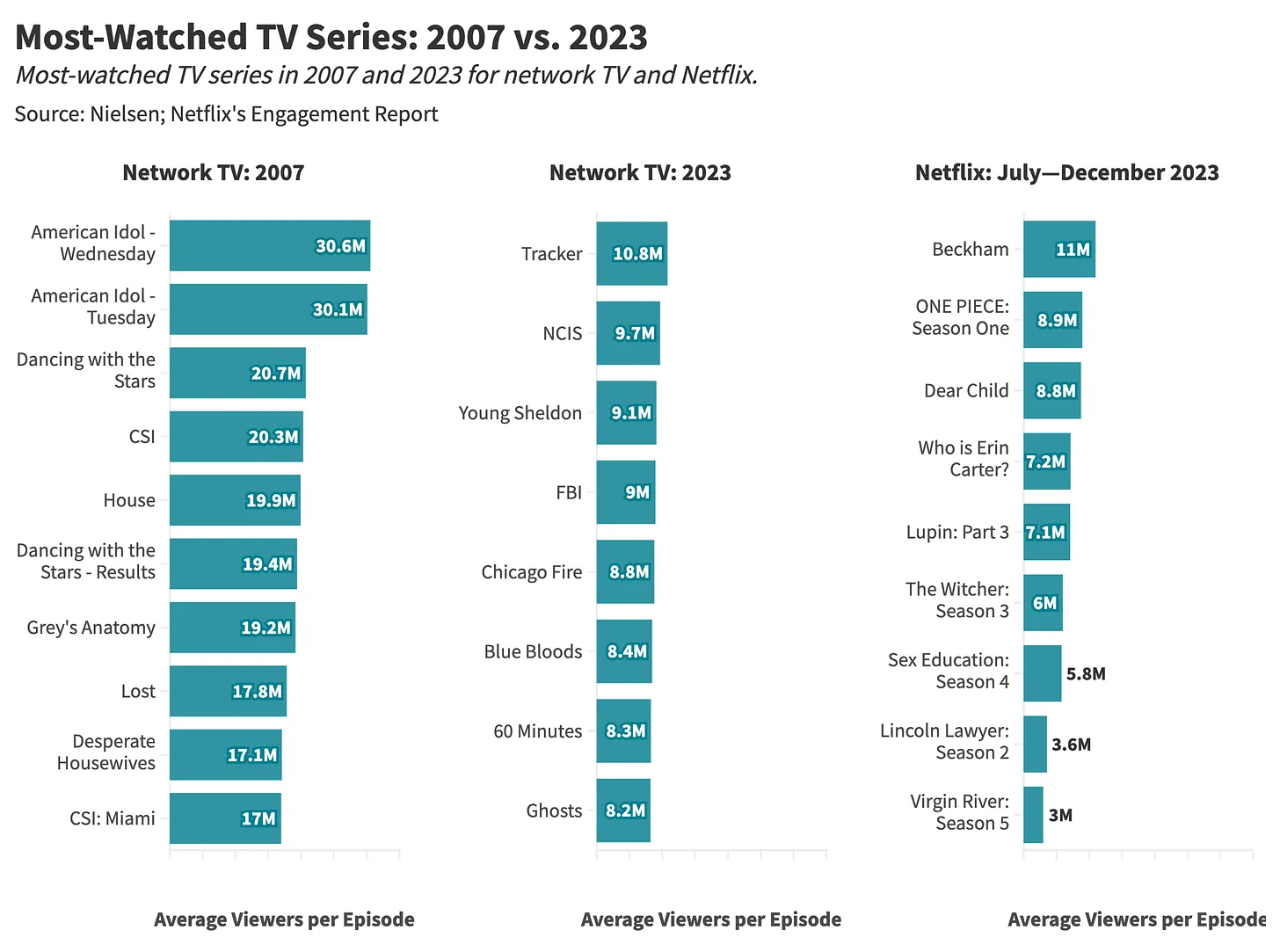

In 2007, game shows like American Idol regularly attracted tens of millions of live viewers, while pre-recorded entertainment like "CSI," "House," and "Lost" saw ~20M viewers per episode. Today, these audiences are split across a variety of programming options, with primetime pay TV shows like "Tracker" receiving 10 million viewers per episode and top-performing Netflix content like "Beckham" receiving similar per-episode viewership (though this consumption is asynchronous).

Streaming hits like "Squid Game" or "Ted Lasso" occasionally crossover into the zeitgeist, forging brief moments of simultaneous enjoyment. Still, most of Netflix's programming is a testament to content breadth—a long-tail of options that consume your time in the aggregate.

With the exception of sports, everyone's content diet is personalized—consumers can choose their own adventure. Overall, this is better; people shouldn't be forced to watch "CSI: Miami" because it's the only thing on, and increased variety ensures greater representation.

Still, there was something about those monocultural "American Idol" and "Lost" broadcasts, the thrill of an entire country (or the entire world) watching these dramas play out in synchrony, and the expectation that you could discuss these programs at work or school the next day.

Today, the proverbial "water cooler conversation" is reserved for recommending the 800th streaming docuseries and goes a little something like this:

- Person A: did you watch [insert name of true crime docuseries]?

- Person B: no, I've been watching [insert name of different true crime docuseries].

- Person A: well, you should check out my true crime docuseries; it's on Peacock.

- Person B: What is Peacock?

- [End Scene]

While this exchange is fictitious, I just overheard a near-identical conversation (while writing this sentence), with "Person A" recommending a music docuseries on Apple TV.

In a fragmented culture of boundless content, we speak in recommendations, no longer capable of discussing shared cultural experiences (outside of Super Bowl commercials!).

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content? Subscribe to Stat Significant for free, and receive new data essays every week.

Final Thoughts: Why Miss Something That's Worse?

[Image: "Survivor" (2000). Credit: CBS]

In August of 2000, my family was on vacation in a remote beach town when my father had a startling realization: we had no way of watching the season finale of "Survivor." "Survivor" was in its first season and had become an instant cultural phenomenon, ushering in an era of high-stakes reality game shows like "American Idol" and "Big Brother."

We had the ability to tape the finale, and yet there was an urgency to my father's mission: we had to watch this thing live. Consuming this program after the fact would nullify its entertainment value.

My family walked around this beach town asking locals where we might be able to watch the telecast, only to be told "No" or asked, "What is 'Survivor'?" We ended up watching the finale on a portable television offered to us by the hotel manager, our entire family squatting in front of a black-and-white screen no larger than 12x12 inches. We watched a low-fi transmission of this tense season finale and had no regrets—this was way better than watching the broadcast after the fact (on a normal TV).

Years later, we would Tivo "Survivor," then record it on DVR, and now you can watch "Survivor" on Paramount+. Some people still have "Survivor" watch parties, but this show, along with most other content, is now consumed asynchronously (at your earliest convenience).

Over the past two decades, I've experienced 40 permutations of home entertainment's latest and greatest—DVDs, Blu-rays, HD, 4K, dial-up, broadband, 50-inch flatscreens, TIVO, Direct TV, Peacock, and so on—with each innovation promising to be the most optimal format or service for my viewing pleasure. I've come to accept that all entertainment products are transient; what I pay for now will eventually be supplanted by something better (that I'll also pay for). With each (ostensible) upgrade, I embrace convenience and better content while losing some valued idiosyncracies in the shuffle.

Is it wrong to miss an inferior technology because you long for the secondary effects posed by its inconvenience? Is it okay to feel misplaced nostalgia?

There was something oddly unifying about watching the same thing at the same time—to know you were consuming "CSI: Miami" and "Bones" while your next-door neighbors were doing the same. There was a quaint sense of community to can't miss television, even if the "can't miss" part was forced upon you by the realities of limited programming and time constraints.

On the one hand, cable's demise is yet another catalyst for growing cultural fragmentation—consumers can shape their own realities within comfortable content silos. On the other hand, there is less of a chance that one television program will single-handedly wreck New York City's plumbing—so I guess there's a bright side to everything.

Enjoying the article thus far and want more data-centric pop culture content? Subscribe to Stat Significant for free, and receive new data essays every week. Want to chat about data and statistics? Have an interesting data project? Just want to say hi? Email daniel@statsignificant.com

About Daniel Parris. Daniel is a California-based data scientist and journalist who writes about the intersection of statistics and pop culture. He initially majored in film, working briefly in the entertainment industry, before a 6+ year stint at DoorDash, joining the company when it was ~150 employees.